At left side of homepage of Fragrantica website you notice a long list that hosts newcomer perfumes and perfume houses. Many enter this galaxy, but only few engrave their names, I strongly believe. They are those who work with precision and aesthetics, not trends and preferences of market. For me Parfums MDCI is a good example of a success. An indie-niche house of perfumes, bigger than many renown “niche” ones. Their high-end quality, complexity of compositions, loyalty to classics, and hunger for ultimate beauty feed my high expectations.

Many of us just know a name and nothing more: Claude Marchal. This is because this brand is out of hype trends. Mr. Marchal is the owner of brand and creative director of MDCI perfumes you have in your wardrobe.

More than his exquisite fragrances, his friendly personality and impressively dedication to his business impresses me greatly. I have the rare privilege to interview with him and I deeply thank him for being so kind to answer my questions patiently.

1. Thank you dear Claude for slicing your time for this interview. Let’s begin with a classic question: Who is Claude Marchal?

I was born long ago in Alexandria, Egypt. I was lucky to grow-up in a home filled with art and antiques, not worth a huge fortune, but still very nice mix and a real cultural treasure.

With a little gift for drawing or painting, I thought the natural path would lead me somehow, somewhere and the first idea would be why not be an architect, or a publisher of art prints etc.

At the same time, I soon became aware that even if I wanted to be able to keep, preserve and grow this heritage, and be free from all sorts of imposed constraints, I would have to work hard. After a short bout with architecture at the School of Fine Arts (Les Beaux-Arts) in Paris, I switched to business, starting with a business school.

One thing leading to another, after my serving in Syria during my military service from 1976 to 1978, I found myself working for an ad agency, then for a major aircraft manufacturer, then five years later was hired out by a company that owned a number of fragrance and cosmetic brands and needed someone to take care of the business in the US.

This was I must say a violent cultural shock, from jets to soaps, creams and scents, but the pay was great, the job description was exciting (it included among other tasks the management of a team of young sales women in the Caribbean :O)) and this was also the opportunity to travel a lot, and learn something different.

Finally after five years of survival in the jungles of corporate world, I understood that I would be happier and better off alone, and do what I wanted how I wanted at the helm of my own business, even small.

Difficult to start building a business or fighter jet in your garage, but starting a fragrance project at home was, at that time, the mid-nineties, very difficult but possible full of promises: unaware, with a very personal idea of what I wanted to do, that I was at the right place at the right moment, to catch the “niche” fragrances wave.

This field was a great opportunity to combine creativity and independence. And taste the joys of the entrepreneurial adventure, and what an adventure it was, and still is!

2. Great introductory! You now have a whole range dedicated to classical compositions. Classical bottle design and sculpture caps. You also name them after great works of literature and music. Seems your background in arts and music plays a great role in inspirations. The question is what in perfume industry make you prefer classic compositions?

I am not obsessed by classicism. I live in a very modern house. However yes, I like beauty, and I can tell if something is beautiful or not. (For me, of course) But it does not necessarily have to be classic: there are some modern art pieces that I would kill to have.

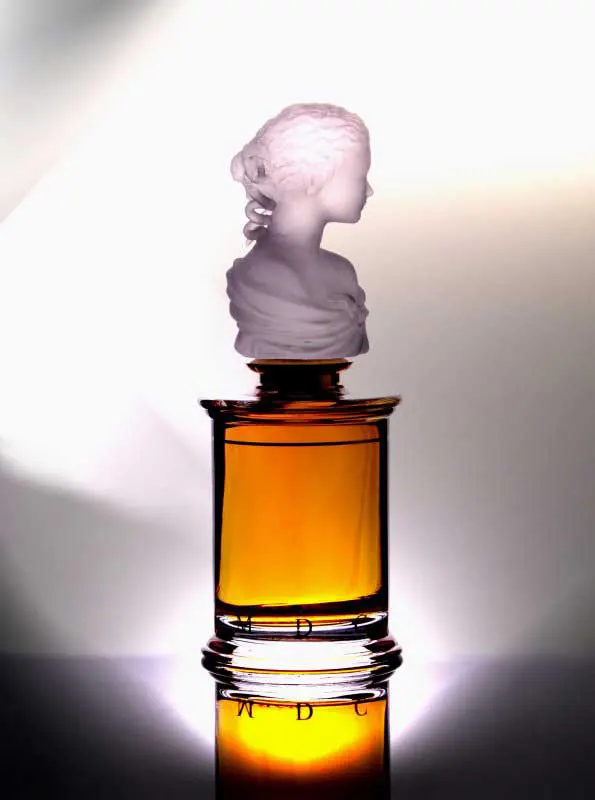

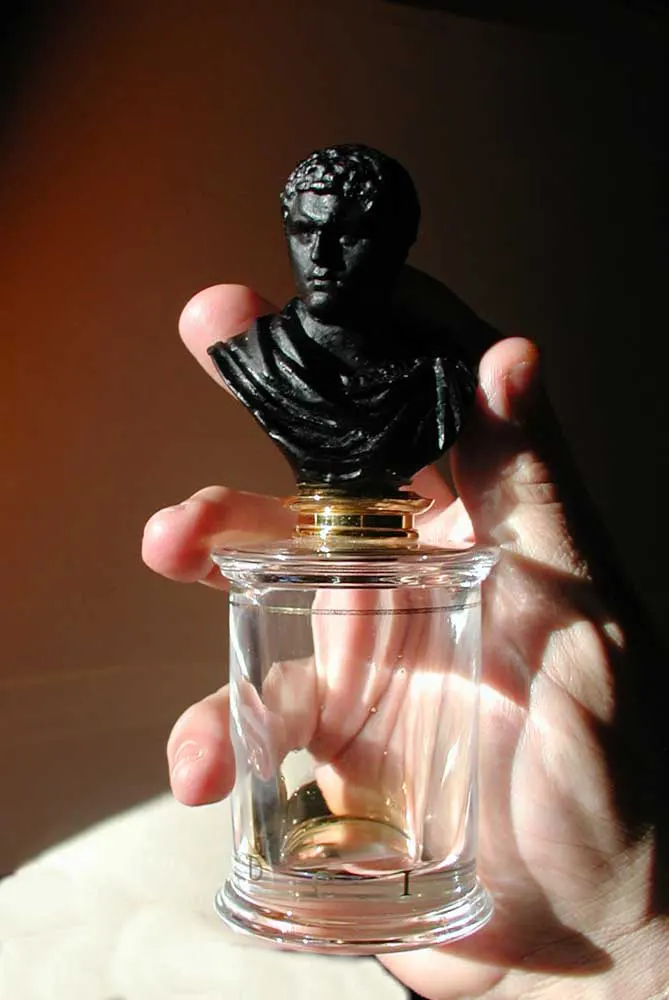

As for my bottles and their unusual stoppers, they are the result of a conclusion that, at that time (the mid or late nineties), perfume bottles were more and more industrial, plain, ugly, specially compared to what the French perfume industry had been able to produce with Lalique and others.

To bring back the romance, the sense of luxury that in my opinion, HAD to go with perfume to satisfy the taste and expectation of a part of customers, bottles had to be «nice». Think of a Ferrari, the engine (the fragrance) is superlative, but the body (the bottle) is almost as important, or even more. Not that I ever thought my «work» could be at par with Lalique’s, but I felt the need, the urge, to bring to market something, an object, that would be an object of beauty. At least in my eyes.

So I simply drew from my environment. When it comes to perfumes, I must admit that in the early days of what would become the brand, I had no preconceived idea or demands, nor was I a perfume fanatic or expert. However, I felt all I had to do is trust my senses and I would be able to sort between bad, average and «good» perfumes. It worked with Pierre Bourdon’s Ambre Topkapi, it worked with Stéphanie Bakouche’s Invasion Barbare, it also worked with Francis Kurkdjian’s Enlèvement au Sérail, Promesse de l’aube and Rose de Siwa, and those that followed. Are they all classics?

Don’t know what that means, after all. They are classic in that they are wearable, and don’t bear silly of offensive, even obscene names in an effort to be noticed. Also, I don’t like to follow trends, being more a contrarian. I don’t like the idea of doing only do «what sells». So I did not venture into oudhs or similar scents while everyone jumped in the bandwagon. So much so that the general style of the bottles did not fit well with anything too «Arabic» or too «young-timer». I would say that this little brand of mine is at the same time, «artistic niche» (in that lots of creativity goes into it), but also a luxury brand.

3. Let’s do a flashback. Any specific background or memory with perfumes from past that you find important in your path in perfumery today? Specially I wonder if your birth town has participation in your olfactory identity.

Claude: Yes, I do have a very acute memory of a very special olfactive moment. I was perhaps four or five, and was seated next to my mother in a propeller aircraft (probably a Super Constellation) on its way from Egypt to somewhere, most certainly France.

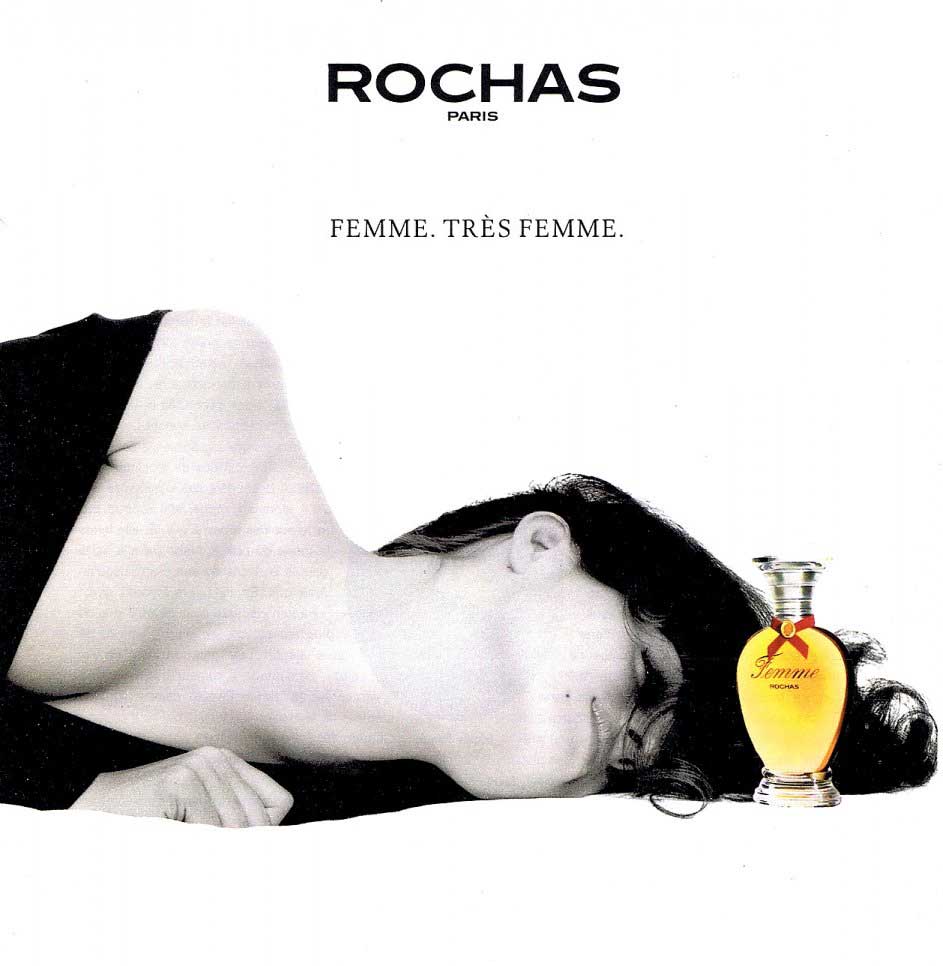

I remember clearly that it was a night flight, and that I was scared by flames spit in the night by the engines at take off. The plane was a world of odors in itself, with odors I had never encountered before: the fabric of the seats, the air, the metal parts, etc. However, this is not what struck me. What struck me was the perfume of a woman seated not far from us. For years, I could not put a name on it, even if it was in no way an obsession, it was there, I acutely recalled the scent, which was different from all those of my mother, and her favorite, Femme de Rochas.

Decades later, I was walking in some street in Paris and there it was, intact, absolutely identical: the scent was the perfumed trail of a woman I had just crossed, and I could not refrain from changing direction and follow her. However, of course, being civilized and polite, out of the question to talk to her, and after a moment I abandoned the magic trail. I was enchanted to have met “The Scent” again, wondering if I would ever have an opportunity to cross its path again, or how I could ever find out what it was.

Many years after, I crossed the path of “The Scent” again, and this time things were easier: the woman wearing it was a family friend, so I was able to ask. The scent, the fragrance was L’Heure Bleue de Guerlain. It would have been even better had it been Vol de Nuit (Night flight), but no, it was L’Heure Bleue.

4. Stunning scent, and I have soft spot for Vol de Nuit too, or say I love that more than L’Heure Bleue. Now let’s come to a question that changes the path of interview: As creative director of MDCI, how do you handle creation of each perfume? Do you guide noses after you handed out brief? This might also be question of many other people about how a perfume is processed.

Claude: The question of how “brands” obtain the fragrance market is one of the big secrets of this industry. I may be wrong, but to me 99% of “brands” work with perfumers whose job is to create fragrances, and very few “niche” brands are in a position to create their own.

Marc-Antoine Corticchiato is one, a true creator and the head of his own house. Francis Kurkdjian another (but backed by a big lab such a Takasago).

Not being a trained perfumer, I have chosen to ask different independent perfumers, or not independent perfumers working for labs willing to invest time and resources in the development of fragrances unlikely to generate large volumes of sales. It started in 1999 or 2000 with Pierre Bourdon, followed by Francis Kurkdjian, then Stéphanie Bakouche and others.

Not relying on a single source allows to have the possibility to find different styles, each “nose” having his or her own personality and way of doing things. And as with any kind of artists, inspiration comes and goes, so better have the broadest possible base of creators.

Not that simple, as they are not that numerous, and that with time and experience(s), one comes to really appreciate working with one or another.

About “briefs”… At the very beginning, the bottle was the brief. I had no real experience with fragrances besides being an executive working for a large company in the beauty/perfume industry. I only had a concept in mind and the will to do something honest, luxurious, far from the industrial stuff mass-produced by the big players.

I asked P. Bourdon (to whom I was introduced to by a friend of a friend of a friend) if he would be willing to create a fragrance that would be coherent with a number of parameters (price, target, still very vague at that time), and that was it. After receiving from him a number of samples, I picked the one I liked the most.

For Francis K, I simply asked him to create one feminine scent of the same quality or in the spirit of Femme de Rochas. He gave me three, so good, I liked them so much that I decided to keep them all that became Promesse de l’aube, Rose de Siwa and Enlèvement au Sérail.

All Stéphanie Bakouche knew was my bottles. I did not have much to show at that time, other than my (empty) crystal bottles I was trying (and did manage!) to sell to collectors. After a short encounter on a perfume bottle show, she sent me a few samples, among which I spotted one that I really liked. Everyone around me told me it was horrible, unwearable, too risky etc. The sample became… Invasion Barbare! So, all I did was to select fragrances that I liked among those that were proposed to me. Chance plays a big role in this.

I worked differently with Anne-Marie Faugier and Bertand Duchaufour. In that I was a little more specific with them in terms of directions and olfactive choices, but in the end, after some tuning, each had the last word. This is how “Vêpres Siciliennes” and “La Belle Hélène” were born.

“Péché Cardinal” was a diamond in the rough spotted among a dozen of samples provided by Robertet. The one I liked the most. I thought it could be fine-tuned in some way, but in the end realized that the first, original sample was the best.

With time, I became more able to put words on what I wanted (words and fragrances don’t mix well), and I was able to be more clear, if not directive or specific. Remember, we deal here with artists, not engineers (which they also are).

Some perfumers are very pleasant and easy to work with, and seem to understand immediately what expect, and consistently deliver very finely crafted scents. However, new players emerge every now and then. I don’t want to depend exclusively on the same few perfumers, as good as they may be, talent is varied and may come from unexpected places.

For the new collection currently in the works, there is indeed a real, clear brief: such or such classic painting I chose for the emotions or pleasure I feel when in their presence. Cécile Zarokian is one contributor, but other perfumers with whom I had not worked before have worked on the idea. My role here is limited to deciding the right concentration, or in a very limited way, to suggest such or such minor adjustment.

Of course, I decide whether such or such proposal by such or such perfumer meets my criteria: is the fragrance good enough? Is it coherent with the brief ? and the most important: do I like it?

So in the end, I pick and choose what I like among all the proposals received, pretty much as I would select paintings in the workshop of an artist. I know a number of such artists, in the MDCI house are walls waiting for paintings of such or such size or style, and I do my little shopping.

To take another image, I think that a brand is much like a book publisher. The work consists a lot in searching the right new writer, the interesting novel, and sometimes, rarely, does the publisher take the liberty to ask the writer to change something. But the publisher is the vehicle, the tool that allows a writer to meet his or her public, same for perfume brands… The last word is the public is, who decides to like or not, to buy or not.

5. By this answer you also answered two extra questions, so I skip over them. A question regarding perfumers: Is there a nose you found fit to MDCI profile and you wanted to work with, but you could not yet, by any reason?

Claude: There is no specific MDCI profile, or style, to me all that matters is if a fragrance is good or not, wherever it comes from, and that… I like it.

In general, I don’t like chasing perfumers (nor anyone). Fate or my good luck put some on my path. I did place a cold call with Francis K. back in 2003 or 2004, but this was another times, I would not do it today.

Interestingly, one of the perfumers who has contributed with several scents for the “new collection” called me, out of the blue: I had never heard of her, not because she was totally new to perfumery, by far, her resumé was impressive.

Another factor is that the little house of MDCI being… a little house, volumes at stake are limited and don’t interest some players, who can also be out of my means in terms of demands. The idea that I could be told “no” being unpleasant, I just don’t knock at doors I don’t know.

6. Classics is what we know MDCI with. I see a Renaissance style in your arts – however you mentioned you’re not obsessed with – yet they are polished and apart form hard and brutal animalic scents that is commonplace feature of works of past. The question is: animalic scents seems to be the current fashion to go for some years on, and grab customers attention. Is there a possibility to come up with an animalic perfume for MDCI?

Claude: The answer, is : YES ! I have a great, brutally animalistic scent to go with one of the paintings selected for the “new collection”. This painting is a perfect pretext to venture into scents too “exotic” or “Arabic” for the “classic MDCI”. And I find this one just… fantastic. Does not necessarily mean it is unique, one-of-a- kind, but this one is mine.

7. That’s great news. Also the painting is great. Géricault’s works give me impression of a mixture of Caravaggio and Delacroix.

I’m impatiently waiting for the new collection to launch. I don’t ask about this new collection to not spoil the surprise.

Now let’s talk about bottles. The recent years we notice that everyone in the perfume industry – even mass markets – releases in uniform flacons. This at one side imitates prestige of niche brands, at the other side greatly reduces expenses.

As a niche brand you have your cylinder flacons, but you also have your creations in 100ml flat square printed bottles. Is that exclusive to Middle East region only? Could you please talk about it?

Claude: The bottles are as important maybe as the content, as they are crucial in the purchase decision process. Again, think of the body of a car, it tells a lot about the brand, the fragrance (cheap, young or the opposite, etc) and… the customer!

At the origin of my brand, the bottle was central in the decision that someone had to do something about the disastrous trend towards bottles that would please glassmakers, talentless designers and accountants. l drew mine on a sheet of page of paper in a few seconds, had a plexiglass model made in New York (I lived in Miami at that time, very very far from anything related to the making of a perfume).

Followed years of efforts to find the right glassmaker (in France) able to produce the bottles in small quantities (the semi-automatic method, which is actually almost manual). The problems I met drove me mad, the quality was at best erratic, and catastrophic delays the norm.

Salvation came when I stumbled upon a very capable glassmill in… Korea that is still my supplier. High quality, regular capacity, impeccable in every respect…

The square 100ml bottles are another story. At one point, I became interested in the Middle East market where every brand but mine apparently had huge business success, and thought that a design I had in mind could be the solution. I like drawing (like you!), and the creative stage is one of my favorite moments. So I took a pencil and drew several sorts of decorative patterns that would adorn, in gold, some kind of a bottle likely to please customers in the Middle East.

Looking for more and better ideas, I search in different museums and libraries in Paris, and in a book on antique oriental fabrics the perfect carnation flower I wanted (part of the pattern of a splendid Ottoman 15-17th century silk fabric).

Back to my pencil, and Photoshop, after much botched efforts I finally obtained the decor that you see on the bottle. Of course I could have commissioned some Art Studio, but first I of course don’t have the kind of money implied, than I just love the creative part, and would never let anyone do it in my place. I am sure that you understand!

All this took a lot of time, and some $$$, sunk into the botched development (in China…) of a metal decorated plate that would be glued on the bottle (black background and raised decor). Very attractive, but too expensive and dangerously sharp. The 100ml bottles supposed to be mainly for the Middle East markets, are nowadays sold everywhere. They are the result of a real need (reaching more clients) and the pleasure I drew from the creative process.

Forgot to mention that most niche brands take shortcuts and use stock bottles. For the cylindrical bottles, I invested almost all my savings in several molds, one for semi-automatic production (a mess), and another for automatic production. This means a lot of research, headaches and… money.

I was sort of compelled to succeed, and there were no blueprint on how to, and no way back. I really believed in the future of “alternative” brands, at a time when the same suppliers who are all too happy (and eager) to provide parts or bottles to anyone, then were not really prompt to accept my requests or supply a minuscule and unknown company, the quantities involved were way too low to interest them. Now that they have been squeezed to death by big brands or big groups, this is another story.

8. Coming to sculpture caps; the most prominent identity of MDCI bottles. Where the idea comes from? We discussed it before and I know every details about it, but our audience may not know about it.

Claude: This a long story, specially if I have to enter into the details of a journey of more than ten years paved with disappointments, frustration, botched attempts, pitiful or pathetic failures.

The idea was simple, and cannot, or does not need much explanations: I simply found the idea that a classic sculpture on a column would make a nice, interesting, unique, class and attractive bottle, and with my parent’s collection of antiques in mind, I started to work on it, back in 1994.

I had no idea that it would be that difficult: in general, sculpture IS difficult, and coming up with something decent and not completely ridiculous or kitsch, even more.

It started with the female figurine: my clumsy efforts, sculpting in resin, putty, or clay led to nowhere (see this old photo dated 1998 showing my first attempts) and I settled on the masculine simply because many masculine antique busts could serve as a model. Important was not only the copy work, but choosing which one would be right.

Soon the contrarian in my decided to say away from anything too Greek and too easy, too aesthetic, and I chose instead the cruel, brutal but so expressive bust of Emperor Caracalla that can be found in the Louvre Museum, the Vatican museum and some others, abundant copies being easily purchased for a few hundred $.

Creating the figurine took years, and duplicating it became the next problem: In what material? How? Metal? Plastic? Clay? Plaster? Concrete? Resins? Moulds for injected plastic were horribly expensive, well beyond my means, the result might feel cheap. Other solutions were already available such as additive manufacturing (stereolithography already existed but was – and still is – imperfect for my stoppers and/or prohibitively expensive).

I decided to try crystal, the first bottles being also in crystal, invested in a steel mould that cost me the equivalent of a nice used car, and the result was… a total disaster, really horrible. In the meantime the glass-mill I had commissioned for my bottles went down the tubes, and I had to find another one. I tried with Daum Studio; nobody there was interested whatsoever. I tried with Lalique and Baccarat without more success, and finally stumbled upon another one, an ancient crystal-mil in the East of France, supposed to have the know-how of Daum for crystal sculptures.

As a matter of fact they had absolutely no experience, and I had to re-invent the wheel with them. After two years of failed trials, they managed to produce about a hundred bottles, and a few more decent many masculine bust-stoppers, for each of which I made the original waxes, and that I finished myself at the factory with fluorhydric acid, sanding, milling etc.

A nightmare that I really enjoyed, being in a crystal mill, dealing with the workers was an incomparable and unforgettable experience that made the early wake-ups, the dozens of 800 km back and forth trips in my old Volvo worth it.

In the end, the crystal masculine figurine was OK, I was able to select and sell the best, this is how I held and was able to finance the rest. For the female version, even after lots and lots of research and visits too many museums and libraries, I had found no satisfactory models in terms of the style I wanted, too Greek, too 18th century, too Italian, too French, too 19th century, too this too that etc…

So I decided to make it, to create it myself, and embarked in another journey of several frustrating years. I’ll hide till my last day the cartons full of ugly failures resulting from these clearly efforts, but in the end, one day, added exactly the right amount of plaster on the cheek of my little lady, she did not look as if she had toothache or crossed eyes, and there she was, lovely, gentle, cute, not some arrogant goddess or fashion model :o) :O)

Crystal caps being way too difficult to make and expensive, and the second crystal mill also gone bankrupt, I looked for some other solution, and found that stoneware, or white hard china could be a nice alternative: another trip of several years into the unknown, as no porcelain or stoneware factory in France was willing or able to do what I expected. So there again I came to the conclusion that the only solution was to learn the techniques and manage to produce the figurines myself.

I invested another big chunk of money into special plaster moulds, imported from England. The purest, whitest possible liquid clay, turned the living-room into a workshop, rented a kiln found not too far from home to bake the figurines, and managed to produced hat I still consider the finest sculpted caps I ever made.

Painstaking, tiring, time-consuming work, frustrating problems with shrinking, deformations before and during firing, breakage etc, but I loved making these stoppers. Made about 1500, sold them all, which financed the survival and growth of what later became “a brand”.

Last stage, the current resin figurines: there too, it took literally years to find the right material (that would not feel like plastic, nor turn yellow with light or perfume, that would express quality, the right formula to avoid bubbles or shrinkage, the right techniques and the right partner able to produce these things that are deceivingly simple). I still finish each piece myself by hand.

Why so much efforts will one ask? Well, the idea of leaving in this valley of tears, after I am gone, for only lasting trace things that would not be well made, that would be ridiculous or just plain ugly is unbearable. I’ll never forget perfume bottle show in Orlando, Florida, during which a lady, staring at my very first (and quite perfectible) bottles and crystal caps, stopped and said to me: “Not good enough!” and turned away. Never more! So these stoppers had to be right, or would simply not be.

I made the originals in plaster, real size plus x% for shrinkage of the wax to take into account how the wax shrinks as it cools and hardens. I needed perfect originals, at the exact right size, to be able to duplicate them in wax, and later to be able to make the moulds for the bisque or ceramic versions. This took years!

Actually I am still working on the same two figurines, improving this or that. I am very familiar with digital imaging and 3D manufacturing, and was almost a pioneer of sorts, but nothing replaces the hand and the eye when it comes to do something “artistic”.

In short, when you start working with soft materials (silicone, wax, melted crystal, resin, you name it) and 3D, you have to overcome issues of dimensional stability (during cooling, during drying, during firing etc). So all this was devilishly difficult, so much so that the “style” was fundamental, specially for the little female figurine that had to go with the fierce Caracalla.

In the end, the style is… pure Marchal :o) I also had to produce giant versions for each bust, for store displays. Another fight that took years before I could find a craftsman able to make them correctly. But I think that you have now a pretty good idea of how much all this took, and why I am so attached to these things. However, they are only a small percentage of sales, most sales come from simple bottles with tassels (which themselves are a whole story, as they are finished here at home by me, my daughters or my mother in law).

Of course, at the heart of the whole story, are fragrances, the quest, or the hunt of which is an enormous challenge in itself. And each fragrance selected is a gamble, so I have learnt to accept that some will sell better than others. No problem, so long as I like each of them.

But one would ask, why spend so much time (ten years or so from the original idea to the first acceptable bottles and caps), $$, energy simply for bottle stoppers?

Because in this “industry” where the competition is so strong, if you are not different, if you are not “better”, if you are a me-too, if you copy, if you follow, you go nowhere.

To be seen, you have to be different. Not necessarily pretty, but different. And I wanted something beautiful, different, and of a quality that would put my work apart from the industrial stuff dumped on the market by big brands. And as I said earlier, to me, the best perfume in the world needs to be hosted in a nice bottle, not just some ordinary industrial, off-the-shelf container. And being different for me is not to be obscene as some have chosen as their way of communicating, nor to be “modern” and “minimalist”. So I chose a domain that made me comfortable and filled be with satisfactions of all sorts, I chose to follow my personal love and attraction for the arts and beauty.

9. Wooow, ten years of attempt and no give up. That’s a huge timeline! You explained so thorough and left no question. So lets shift to another topic: you had big trouble with establishing your bottles and caps. I wonder if you have ever had trouble with material restrictions of IFRA.

Claude: IFRA: a big pain in the neck, and yes, the origin of many frustrations. I have lost because of IFRA one of the fragrances to which Luca Turin had given five stars, Francis Kurkdjian’s Enlèvement au Sérail that I had to discontinue for it did not meet IFRA’s latest demands (too much oakmoss and some other ingredients, attempts to reformulate the scent never allowed to find the same depth and velvety quality. Mercifully, Chypre Palatin has never been a problem, and as you know, has never had to be reformulated.

10. Talking about IFRA and difficulties, what is the most frustrating and most interesting part of being a creative director?

Well, the answer is simple: The most interesting part of being a creative director is to have the possibility to be creative, and to be director!

Creative means to have total freedom to explore, to try, even to fail. (well, to a certain degree of course) Remember, I am not a salaried or commissioned creative director, I created this brand and own the company on which it is based. This is how I feed my family and pay the bills and taxes France is famous for.

Director means not be free of any constraint, other than those dictated by how the company fares. No boss, no marketing committee, no ambitious colleague competing within the structure. Total freedom.

11. Total freedom! I sometimes dream about it! :O You know it’s not easy to settle in a level and say “I work with total freedom”. It’s admirable and respectable. However, business is business, and one hardly can stay successful without following streams. You’re one of those to example. Oud, orientals, animalics, modern retros… Many trends came and pass and MDCI is still MDCI. How do you stay tuned without being influenced by hyped trends?

Claude: I know how lucky I have been to be that free, even if the price and road was steep. Keep believing in you and your talent, never stop dreaming.

As for trends, I simply ignore them, because trying to keep up would be a full-time job, ruinous, boring, frustrating etc. Add that I don’t want to and let the outer world influence mine.

I am by temper a contrarian more than a follower… However, hype is not only vain and shallow, it also goes with short-sighted search for the latest novelty. And nowadays I am meditative (but reactive) when looking at the state of the market and distribution, overflowing with hundreds of new brands built on the shallowest of pretexts, most often the chase of quick money or fame an only rarely with real passion and creativity.

Of course, competition is good, each year a nugget or two emerges, but I feel, with this proliferation, that the whole category may be losing its luster and magic.

12. I see. Today’s perfume industry looks like a unarranged mass, sadly. In such tournament if you want to introduce MDCI with only one perfume of your collection which one it would be?

Claude: Don’t know, I like them all and it would be like choosing one of my children!

13. Is there a perfume out of MDCI you wish you would have created?

Claude: An amazing oudh smelled in Dubai back in 2012.

14. May I ask its name?

Claude: That perfume in Dubai did not have any name, it was shown to me by a local in a beautiful local blue and gold glass bottle.

15. And the final question: How do you describe Parfums MDCI with only three words (adjectives)?

Claude: Three words… ouch, this is a tricky question. What these three? Different, Elegant, and Personal.

Thank you again dear Claude and thank you all for reading this interview.